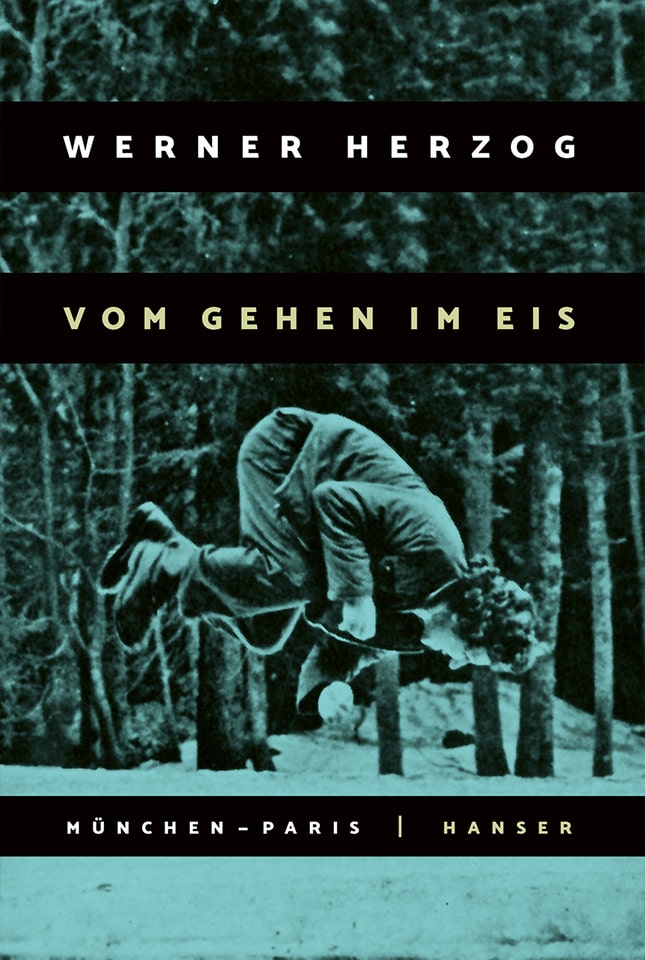

A poetic meditation on life and death written in the cold silence of a winter walk.

»Rain, rain, rain, rain, rain. It is nothing but rain. I can hardly remember anything else.«

In November 1974, after hearing that his mentor Lotte Eisner, the critic and film archivist, was dying in Paris, Werner Herzog decided to walk all the way there from Munich. He did so »in complete faith, convinced she would remain alive if [he] came on foot.« During the travel he documented his surroundings, his emotions and his encounters, capturing everything from the pain of the long walk to moments of intense wonder.

Werner Herzog was born in 1942 in Munich and spent his childhood in a remote Bavarian village cut off from the world. He often describes that time as one that forced him to develop endurance, imagination and a stubborn belief that he had to carve out his own path.

He did not see his first film until he was a teenager. Cinema was not a nostalgic childhood memory for him but something he discovered late. From the moment he understood what film could be he wanted to make films rather than watch them. He worked odd jobs, wrote scripts and pushed ahead with an intensity that was more instinct than plan.

In 1968 he completed his first feature, Signs of Life. The film won a Silver Bear at the Berlinale which did not make him famous but it placed him on the map and, more importantly, it caught the attention of Lotte H. Eisner. At this time Eisner was a central figure for young German filmmakers. She had survived exile, she felt the absence that the Nazi years had carved into German film history and she worked as curator and critic to preserve what still existed. She saw Herzog’s film and said, this is absolute German cinema. For Herzog this was more than praise. It gave him a sense of belonging and responsibility. Eisner became a bridge to a tradition that had almost disappeared and someone whose judgment carried real weight.

Above you can see the self portrait (1986) by Herzog. The important part begins at 6:26, where he talks about the book, which he describes as one of the most special among the many he has written. What follows is a short dialogue with Lotte Eisner.

Between 1968 and 1974 Herzog moved restlessly, making films under extreme circumstances and at great personal risk. He was not yet the celebrated director people know later. He was a young filmmaker trying to define himself, often misunderstood, often broke, but driven by a need to test the limits of what cinema could do.

To truly understand Werner Herzog’s On Walking in Ice, you need to understand the motivation behind his journey: Lotte Eisner. She was not only important for Herzog, but also a cornerstone of German cinema during a time when the industry was lost after the Nazi era.

Filmmakers like Werner Herzog and Wim Wenders owe much to her; she preserved critical film history, supported contemporary cinema through her writings and work as chief curator at Cinémathèque française. Her work highlights the fact that cinema’s survival depends not only on the filmmakers but also on those who safeguard its legacy.

By 1974 Herzog was part of the New German Cinema but still very much an outsider, someone whose films felt strange and uncompromising. Eisner validated his instincts and gave context to what he was attempting. He was still in this phase of becoming, still a filmmaker who relied on her presence as an anchor. It was not only an act of devotion but also a way of holding on to the thread that connected him to a cinematic heritage.

In his diary Herzog details injuries, obstacles and harsh weather drifting into memories. Snow turning into rain as he approaches Paris, relentless cold and grueling terrain. He is not often met with hostility, the police and locals eye him suspiciously. He captures moments and images with the careful eye of an artist, describing landscapes, encounters and death. His reflections swing between the personal and the universally existential. The narrative brought David Lynch’s The Straight Story to my mind, there are some parallels, go find them yourself.

Throughout his walk he constantly sees crows and they drive him crazy. If one wanted to summarise the book with a single painting this would be the one. Loneliness becomes a companion on the journey. Herzog’s encounters are fleeting and he often finds shelter only in unconventional places like construction sites or he just breaks in somewhere. At some point he is rejected from an inn because of his appearance, forcing him to find shelter in a women’s guesthouse. The anecdote of his grandfather who refused to rise comes near the end of the book. He does not explain its meaning, leaving us to interpret it. And he drinks so much milk!

On Walking in Ice deals with the acts of homage we perform for those who inspire us, at times almost naive in its belief in the efficacy of a symbolic gesture. It reveals Herzog’s openness of heart and willingness to let the world in. And sometimes the journey itself is the destination or something like that, am I right.