The church’s bells mark the passing of time.

»Spira, spera«

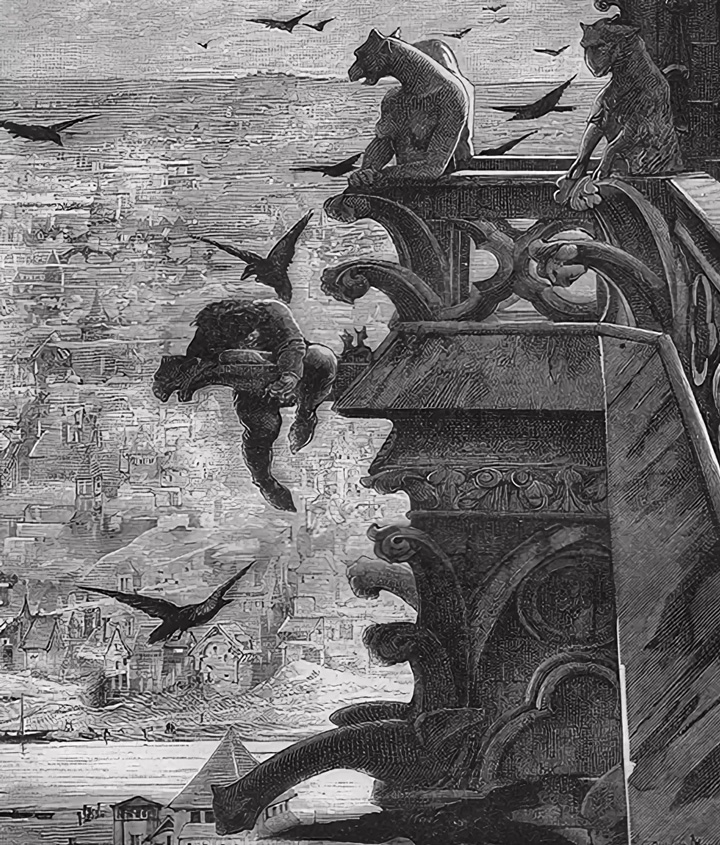

In the middle of Paris, surrounded by the Seine, stands a church that has seen everything... revolt, markets, fires, coronations, hangings. Around it the city moves, loud and alive, while the stones of Notre-Dame stay silent, holding all their stories.

Victor Hugo (1802–1885) was one of the greatest writers of the 19th century and the leading voice of French Romanticism. Born in Besançon as the son of a Napoleonic general and a religious mother, he began writing poetry at an early age and published his first collection while still a teenager. His breakthrough came in the 1820s with his play Hernani, which caused a scandal in Paris but also marked the victory of Romanticism over Classicism on the French stage. From then on, Hugo became a literary celebrity and a political figure.

Notre-Dame de Paris (1831) which is set in 15th century Paris, was his first major novel and remains one of his most powerful works. Hugo wrote it partly as a protest against the destruction of medieval buildings and after its publication, public interest in preserving Notre-Dame and other Gothic monuments surged. Him and his romantic circle essentially sparked a national preservation movement.

His later masterpiece Les Misérables (1862) reflects his growing concern for social justice and the plight of the poor. Exiled for nearly twenty years after opposing Napoleon III, he continued to write and publish from the Channel Islands, becoming a symbol of moral resistance in France.

When he returned to Paris after the fall of the Empire, he was celebrated as a national hero. Hugo died in 1885 at the age of 83. His funeral drew more than two million people, and he was buried in the Panthéon, among the very heroes and thinkers he had admired in life.

I read Notre-Dame de Paris as a buddy read with my girlfriend which helped a lot because it’s one of those books you feel the need to talk about. I kept comparing it to the Disney movie asking myself where the talking stone statues went or why in the second half everyone suddenly starts to slime each other. I didn’t remember it being this brutal.

It’s a dream for anyone who loves history and prose because Hugo combines the two in such an interesting way. He writes about the cathedral as if it were human and about fictional people as if they were carved in stone. When he says that one day books will replace buildings as the keepers of memory, he puts himself in the shoes of the people of that time. If he knew how things turned out today he’d probably be horrified. In Hamburg we have a saying that the city suffered three great catastrophes: the Great Fire, the World War and the Office for Monument Protection.

He describes every statue, every bell, every shadow of Notre-Dame. Hugo knows his stuff and he loves this church. The English title The Hunchback of Notre-Dame actually tricked me. It makes you think it’s about Quasimodo but it’s a bit like My Neighbor Totoro where the creature everyone expects to see, turns up way less. It’s really about that church in the middle of Paris like the original title says.

»Every face, every stone of this venerable monument is a page, not only of the history of France, but of the history of science and art. [...] Everything in Notre-Dame is mixed, combined, fused. This central church is a kind of miracle among the old sanctuaries of Paris; it has the head of one, the limbs of another, the nave of yet another, a little of all.«

The characters move through it like parts of one big living organism. They’re all connected by invisible strings bumping into each other through coincidence and fate. Making a little character list at the beginning of the novel doesn’t hurt.

It also reminded me a lot of Frankenstein: the same loneliness, the same misunderstood creature and an tragic father figure.

Then there’s Esmeralda. Every man in this story sees something different in her: salvation, temptation, danger, but nobody actually sees her. Spoiler: except for Gringoire maybe. And no surprise the poet is the only one who gets a happy ending as if Hugo was trying to tell us something with that decision.

When Quasimodo is whipped and humiliated in public it’s one of the hardest scenes to read but also one of the best written. It’s the turning point. The first two days of the story fill about half the book which was crazy for me in hindsight. The interaction of Esmeralda and Quasi in the tower mesmerized me. It’s the kind of intimacy that only comes from spending time together in silence.

»She saw and heard nothing more of Quasimodo.«

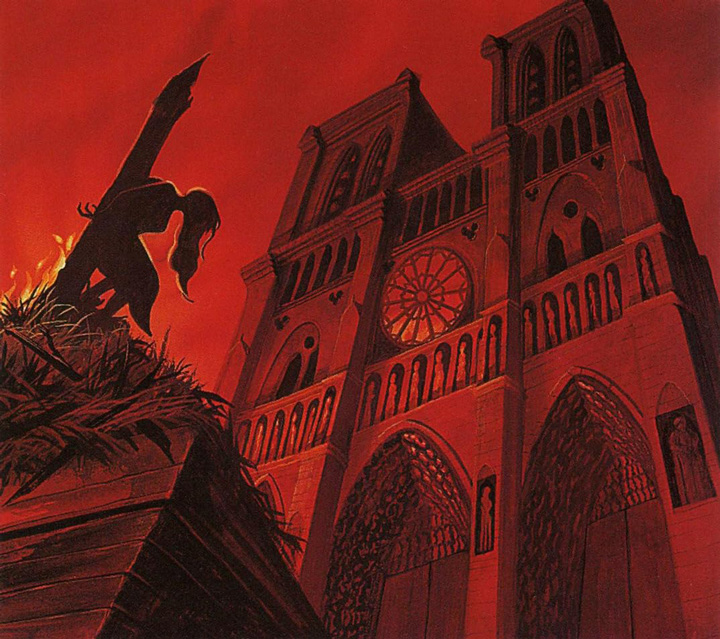

I’ll be honest there were parts where I struggled, especially with the endless descriptions of Paris or the church. But every time the story picked up again, it came together. While reading, I went to Paris myself and visited Notre-Dame. It was still under renovation after the fire. You can’t climb the towers yet, which was a bit of a heartbreak, because so much of the novel happens up there. We also visited Hugo’s tomb in the Panthéon and there were actually people leaning on the tombs, scrolling through their phones like there are no remains inside it. Rire ou pleurer?

While doing some research I came across a famous quote by Goethe where he absolutely loses it over the book (Conversations with Goethe in the Last Years of His Life):

»I have in these days read his Notre-Dame de Paris, and it required no small amount of patience to endure the torments that this reading caused me. It is the most abominable book ever written! [...] The so-called acting persons he presents are no human beings of living flesh and blood but miserable wooden puppets which he manipulates as he pleases [...] .«

Now to be fair Goethe was already over 80 at that point long past his Sturm und Drang days. He had turned to classicism where everything in art had to be orderly and true. And he’s not completely wrong: we don’t get realistic humans here; we get archetypes, almost biblical figures. Goethe’s criticism makes sense for his mindset but it completely misses what Hugo was doing who started with classicism and moved into romanticism.

You can tell from this book that Hugo despised both the death penalty and blind superstition. But this shit got layers. Hugo picks up on all these prejudices against the Romani that they eat people or kidnap children and then just goes yup they did kidnap the child all for the story. And he doesn’t even bother moralizing about it. He shows the ugliness lets it stand and that’s okay.

Finishing it felt like waking up from a long dream. For me Notre-Dame is the bright counterpart to Frankenstein. Both end in destruction but Hugo’s version leaves you strangely calm. The inevitable happens but there’s grace in the acceptance.